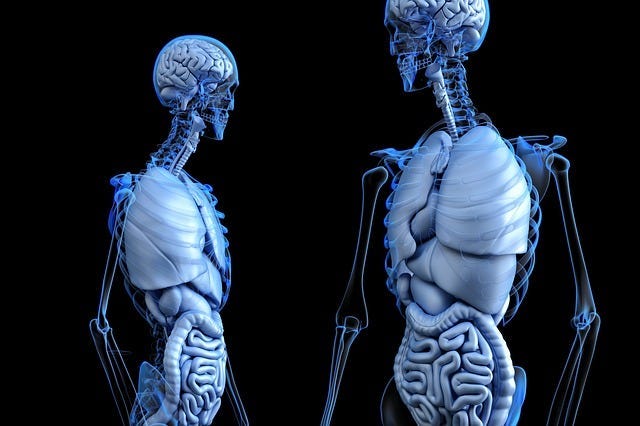

If you have ever thought that your innards appear to have a mind of their own, it’s because they have. Deep within your abdomen is a brain that works semi-independently of the one in your head.

This second brain is teeming with gut bacteria that, in exchange for a warm place to live and plenty to eat, produce chemicals that can profoundly affect your mood. A little bit temperamental, the gut-brain must be handled sensitively.

Gut Bacteria — The Brains in your Belly

Technically known as the enteric nervous system, the gut-brain consists of a network of over 100 million neurons lining the digestive tract. Interacting with those neurons are approximately 100 trillion bacteria, creating a weight of around 4lb.

The gut brain is connected to the head brain via the vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the body’s autonomic nervous system. Think of the vagus nerve as a two-way superhighway, along which messages are exchanged between gut and brain.

The bacteria in your gut, sometimes called psychobiotics, can profoundly influence brain chemistry. Psychobiotics produce neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that enable communication between neurons. Some of these neurotransmitters are involved in mood regulation. One in particular — serotonin — plays an especially important role.

Gut Bacteria and Serotonin

It may seem weird to think that gut bacteria can control your mood, but it’s not so weird when you consider that about 95% of the body’s serotonin is found within the digestive tract.

Lack of the “happy” neurotransmitter serotonin is associated with depression. Commonly prescribed antidepressants — selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — work by maintaining serotonin in the brain.

In the past, researchers did not believe that the serotonin in the gut affected the brain, which has its own serotonin supply. But over the last decade or so, there has been a flurry of research activity, all suggesting otherwise.

“Based on recent discoveries, we suggest that gut microbiota are an important player in how the body influences the brain, contribute to normal healthy homeostasis, and influence risk of disease, including anxiety and mood disorders.”

Those gut feelings are not all in your head; they really are in your gut.

Of Mice and Men

Lack of gut bacteria can result in behavioural changes, an observation seen in animal experiments. When germ-free mice are reared in a sterile environment, normal brain function is negatively affected and they show hightened stress and anxiety responses, together with ‘dramatic’ changes in serotonin transmission.

When their guts are colonized by healthy bacteria, the mice show notably decreased anxiety.

The two strains of bacteria shown to have positive effects are the Bifidobacteria and the Lactobacillus — strains also found in the healthy human gut.

Although most of the studies carried out have been on rodents, experiments with positive results on humans are beginning to emerge. One study on humans published in the British Journal of Nutrition found that, when volunteers followed a 30-day course of probiotic bacteria (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria) they experienced decreased anxiety and depression, and alleviated psychological stress.

The Good, the Bad, and the Not So Far-Fetched

The gut microbiome isn’t always healthy, though, and an imbalance between types of bacteria, often referred to as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, or ‘friendly’ or ‘unfriendly’, can lead to serious health problems.

As well as having a brain of its own, the gut is lined with nerve terminals containing the stress hormones adrenaline (epinephrine, in the US) and dopamine. These hormones are released when you experience stress. The release of stress hormones in the gut enables pathogenic, or ‘bad’ bacteria to proliferate and initiate infection, which is how stress can make you ill.

These bacteria in your gut, usually kept well under control by your friendly bacteria, have developed systems of detecting your stress levels, and using that stress to their advantage.

Your thoughts alone can influence whether or not you succumb to infectious disease.

Beneficial gut bacteria have been shown to calm down anxiety-prone mice. By the same token, stress suppresses beneficial bacteria. When rodents experience stress, in the form of separation, crowding, heat and noise, the composition of their gut bacteria changes. However, when given probiotics, anxiety levels in the bacteria-free mice are reversed.

What cunning little deviants these critters truly are: they hack into your emotions and play with your mind.

Feed your gut bacteria well

By eating the right food, you can tweak the balance of bacteria in your gut in favour of the good guys. You can take probiotic supplements for some immediate effect, but in the long term you should aim for a diet loaded with probiotics and prebiotics.

Fermented foods are a good source of probiotics. Good examples include live natural yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, pickles and miso.

Prebiotics are food components that feed the probiotics. They are defined as

“a non-digestible food ingredient that beneficially affects the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacteria in the colon.”

Prebiotics take several forms, most commonly inulin (a type of soluble fibre) and oligosaccharides (undigestible sugars). They are found together in plant foods. Some of the best sources include onions, leeks, garlic, Jeruselum artichoke, chicory root, coconut, carrots, bananas, carrots, asparagus, yams.

The fibre in plant foods, especially fruits and vegetables, provide prebiotics — the food that feeds beneficial gut bacteria. Certain plant foods, especially the cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, sprouts, kale, and cauliflower), contain compounds called glucosinolates that serve not only as nutritious food, but also stop the bad bacteria from sticking to the gut wall, and hasten their departure.

Ferment your fibre

When you eat foods high in these soluble fibres, they are fermented in your gut to produce short chain fatty acids. As well as feeding your bacteria, these fatty acids have anti-inflammatory properties that also help fight depression. Inflammation in the gut is associated with depression.

Fibre also influences the composition and activity of gut flora and discourages bad bacteria from proliferating. The higher your level of friendly bacteria, the lower your level of the downright unfriendly.

Be aware that some people with IBS-type gut issues cannot digest the fermentable fibres in these foods and should avoid them. For more details, see:

Protein power

Complete protein such as meat provides the highest level of the amino acid tryptophan, required to make serotonin. This action is facilitated by the microbes in the gut. In one study, mice fed a diet containing 50% lean ground beef had a greater diversity of gut bacteria than those feed standard rodent feed of ground soya and corn. They were more physically active, and demostrated better memory and less anxiety.

Bacteria are the future

These discoveries open up exciting new possibilities for treatments for mental health problems, not to mention intestinal disorders.

We’ve come a long way since the presence of vast colonies of bacteria in the gut was first discovered in the late 19th century. People were appalled — and those with nothing better to spend their money on even had their colons removed by the royal surgeon Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, as treatment for what was termed ‘intestinal toxaemia’.

Scientists now believe that alterations in gut bacteria can play a role in the development of human brain disorders including autism, anxiety and depression. Until recently, the possibility that gut bacteria could have this effect had been largely ignored by the world of neuroscience.

It probably seemed to be too far-fetched, surreal even. Now, organisations such as the National Institute of Mental Health are throwing themselves into the race to further research this area.

“The initial skepticism about reports suggesting a profound role of an intact gut microbiota in shaping brain neurochemistry and emotional behavior has given way to an unprecedented paradigm shift in the conceptualization of many psychiatric and neurological diseases.”

Just tweaking the balance of gut bacteria can change your brain chemistry. At the same time, your brain can massively influence the balance of bacteria in the gut: it’s a two-way thing.

Today we have come to terms with the residents within, but are still only beginning to grasp their full significance. Eat right for your gut bacteria — you may find you feel a whole lot happier for it.

Hey Maria, I was interested in your mention of tryptophan and serotonin. I just read an article by a doctor saying that he eats 6 egg yolks a day from chickens that he breeds himself (to keep the linoleic acid low compared to normal bought eggs) but only eats 1 of the egg whites because of the high level of tryptophan which converts to serotonin. I consume a lot of eggs but I've never heard of either of these things being a potential problem before, have you? Also, does the linoleic acid in eggs differ from that in vegetable oils?